Science stories of 2006

It's been a year of little leaps. Nothing Earth-shattering or, at least, nothing the world has noticed yet. Someone once remarked to me that the most important scientific result of the year just gone wouldn't be recognised until several years later, when its implications were much clearer. For what it's worth, here's what James and I thought were the most interesting and noteworthy science stories of 2006. Perhaps the low-key year is an unconscious repsonse to the Hwang scandal - the Korean scientist faked research and papers on cloning and was discovered at the end of last year.

It was also a year of warnings: a worsening biodiversity crisis, the Arctic ice cap predicted to be ice-free in summer by 2040 and UK chief scientific adviser David King making his starkest predictions yet on the effects of climate change. One piece of good news (possibly) on the last front: with British economist Nicholas Stern's report on the potential cost of climate change, will 2006 go down as the year the world work up to the problem?

It wasn't entirely quiet on the discovery front: the spectacular Stardust mission to bring comet dust back to earth; the Tiktaalik fossil (pictured) that gave biologists clues on how animals made it from water to land; and flowing water on Mars. Here's to more brilliance in 2007...

Fish out of water, polar ice, and leakage on Mars

Tiktaalik

A crocodile-like fossil called Tiktaalik roseae, found on Ellesmere Island, Canada, sent scientists wild with excitement. A missing link between fish and land animals, it showed how creatures first walked out of the water and on to dry land more than 375m years ago. Tiktaalik - the name means "a large, shallow-water fish" in the Inuit language - lived in the Devonian era lasting from 417m to 354m years ago, and had a skull, neck, and ribs similar to early limbed animals, known as tetrapods, as well as a more primitive jaw, fins, and scales akin to fish. It showed that the evolution of animals from living in water to living on land happened gradually, with fish first living in shallow water.

Arctic ice

Sir David King, the UK's chief scientific advisor, warned that, unless governments around the world took urgent action against climate change, global temperatures would rise by 3C, resulting in global famine and drought and threatening millions of lives. Cereal crop production could drop by between 20m and 400m tonnes, 400 million more people would be at risk of hunger, and 3 billion would be at extra risk of flooding and without access to freshwater supplies. This year, scientists calculated the Antarctic ice sheet is losing 36 cubic miles of ice every year. They also made the startling prediction that the Arctic ice cap will lose all of its summer sea ice by 2040, given the accelerating rate of melting observed in recent years.

Cellardyke swan

The dreaded avian flu, H5N1, turned up in a dead swan in Cellardyke, Fife. The virus seemed to remain confined to wild birds, however, and the potentially deadly flu caused no human casualties in the UK. It does not mark the end of H5N1, however. Scientists predict it will be back in the coming months and begin to spread around the world again as birds begin migration. For it to become deadly to humans, H5N1 needs to mutate so that it can transfer easily between people. So far this has not happened.

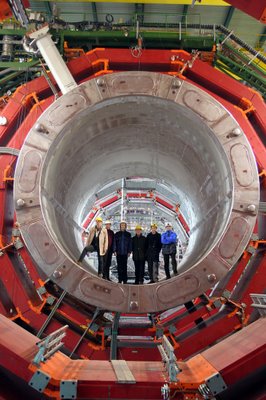

Stardust

Nasa's adventurous Stardust mission brought the dust of a comet back to Earth. The mission was full of firsts: the first time a probe had been flown so close to a comet; the first extraterrestrial use of the advanced aerogel material - a hi-tech mousse made of glass and air sometimes called "frozen smoke" - to trap the grains of dust; and the first successful sample return to Earth since the moon landings. The first results were published in December and showed that scientists would have to rewrite the textbooks on comet formation. Not only are these objects more than simply dirty snowballs, as had been previously thought, scientists found materials in them that suggest they could have kickstarted life on Earth.

Pluto

The underdog planet, smaller than the moon, was kicked out of the planetary club by the International Astronomical Union. The 2,500 scientists of the union decided on a definition of a planet as a body that orbits the sun, is so large that its own gravity makes it roughly spherical, and, crucially, also dominates its region of the solar system. Their decision will force a rewrite of science textbooks because the solar system is now a place with eight planets and three newly defined "dwarf planets" - a new category of object that includes Pluto. The category also includes an asteroid called Ceres and an object bigger than Pluto, initially called 2003 UB313 but later named officially as Eris.

Messing about in space

2006 was the year for doing weird, risky and just plain daft things in space. In February, an old Russian space suit filled with clothes was shoved out of the International Space Station. This was the cosmic equivalent of taking out the rubbish and the zero-G Guy Fawkes eventually burned up in the atmosphere as planned. In July, a Las Vegas property magnate called Robert Bigelow launched an experimental inflatable space hotel. The unconventional inn in the sky was crewed by cockroaches and Mexican jumping bean moths. In November, Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Tyurin hit the longest golf shot in history from the ISS. A Canadian golf manufacturer paid for the stunt.

Water on Mars

The universe may not be such a lonely place after all. Earlier this month, Nasa scientists revealed the first evidence for flowing water on Mars. By comparing images taken by the now defunct Mars Global Surveyor satellite in 2001 and 2005 they saw tell-tale grooves cut by water bursting out of a crater wall and flowing between boulders. Researchers had previously found evidence that ancient lakes once dotted the Martian surface and vast quantities of water are locked up as ice at the planet's frosty poles. The flowing water would have quickly boiled and evaporated despite temperatures ranging from -8C and -100C because of the extremely low pressure. But the fact that it was there ups the odds for life on the red planet.

Extinction fears

In July, scientists warned extinctions are happening at 100 to 1,000 times the natural rate in geological history. Nearly a quarter of mammals, a third of amphibians and more than a tenth of bird species are threatened. Climate change is expected to force a further 15% to 37% of species over the edge. In November we learned that the current rate of extraction from the seas is predicted to cause the collapse of all the world's fish and shellfish stocks by 2048. Another study suggested that tigers would become extinct in just two decades.

Mature mums

The bounds of reproductive medicine were pushed a little further in July when a child psychiatrist became the oldest woman in Britain to have a baby. Patricia Rashbrook, 63, had the boy by caesarean section after receiving fertility treatment in eastern Europe. The birth provoked criticism from groups who said that her age would mean she was not physically able to bring him up.

Neanderthal refuge

Neanderthals may have clung on in Europe until as recently as 24,000 years ago - 11,000 years later than scientists had thought. A cave that was perhaps their last European refuge was revealed in a study published in September. Gorham's cave in Gibraltar was home to 15 neanderthals.